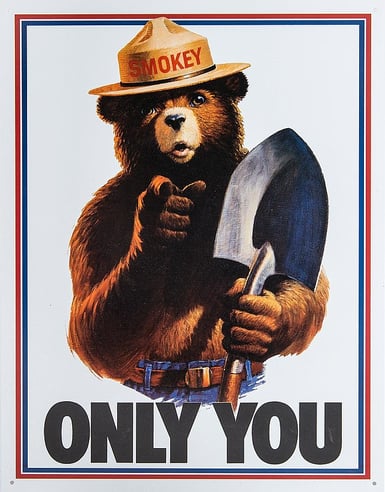

A great big bear stands in front of you, wearing a wide-brimmed hat and blue jeans, and holding a shovel in one hand. He raises the other hand, and points a finger squarely at your face. He opens his mouth to speak—but even before the words come out, you know exactly what he’s going to say:

“Only YOU can prevent wildfires.”

Smokey Bear (technically not Smokey the Bear) is as much a part of the American consciousness as George Washington, bald eagles, and the national anthem. First seen in 1947 as part of the U.S. Forest Service’s Wildfire Prevention Campaign, this stern but warm character has been educating Americans about the dangers of poorly tended campfires, dropped matches, and still-burning cigarette butts for more than 75 years. Throughout that time, he has called on individual citizens to safely steward the land on which they live.

Smokey’s impact on pop culture has been enormous. According to the Ad Council, his famous catchphrase is recognized by an astonishing 96 percent of U.S. adults. What’s more, he has played a key role in the Forest Service’s ongoing fire prevention campaigns, making him at least partly responsible for the huge drop in wildfires seen since the 1930s.

(Indeed, it turns out that Smokey might be a bit too good at his job. In what researchers are calling the “Smokey Bear effect,” the success of the Forest Service’s fire prevention messaging has led to a buildup of small plants and undergrowth in our national forests and grasslands—perfect fuel for the massive, hard-to-control superfires that have ravaged a number of communities in the last few years, particularly in the Western U.S.)

Why is Smokey Bear such an effective communicator of the Forest Service’s message? How has this cartoon mascot endured for so long—and what makes him so powerful that his words have literally changed the American landscape? Finally, what can we learn from the Wildfire Prevention Campaign about how to tell our own stories in ways that dramatically change behavior?

An Iconography of Smokey Bear

At his core, Smokey Bear is a message, or story, communicated through an image: in this case, the image of a bear in a wide-brimmed hat and blue jeans, holding a shovel. We can learn a great deal about Smokey—what he is, how he operates, and why he’s so effective—by relying on tools drawn from the field of iconography.

As Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank explains in her Khan Academy course on art history, the word “iconography” literally means “image-writing” (from the Greek eikon, or “image,” and graphe, “writing.”). In other words, iconography is the study of how images convey meaning—how the objects and characters in a given image can symbolize particular ideas and concepts.

Importantly, the meaning of a given symbol depends on its cultural and historical context. As Kilroy-Ewbank points out:

“To understand the symbols, you have to be familiar with their culturally specific meaning—as in, you need to be ‘in the know’ about agreed-upon conventions.”

An iconography of Smokey Bear, then, will look at both a) what his image means to the people who see it, and b) how the surrounding context makes that meaning possible.

Hats, Shovels, and Dungarees

For instance: what’s the deal with Smokey’s hat? Why that particular kind of broad-brimmed hat, rather than a baseball cap, or a fedora? And why put a hat on a bear in the first place?

Artist Albert Staehle’s choice of hat—technically called a campaign hat—connects Smokey with the Forest Rangers who have long worn it as part of their own uniforms.

More broadly, in an American context, a campaign hat also carries with it implications of authority, discipline, and responsibility. Worn by hard-nosed drill instructors in several branches of the U.S. Armed Forces, as well as state troopers and other law enforcement officials in many parts of the country, the hat conveys the message that the person wearing it should be taken seriously.

All of these associations make the campaign hat a good choice for Smokey, who has a serious message to share. Like a drill instructor, Smokey is tasked with training citizens to manage potentially deadly situations—in his case, uncontrolled wildfires that can damage landscapes and put communities in grave danger. For his American audience, the hat adds a note of strictness to his message, implying that responsible fire management is both a serious matter and part of one’s civic duty.

At the same time, Smokey is not a soldier or a cop. Instead of a clean, pressed uniform, he wears jeans, a piece of clothing historically associated with the working class. As scholar Marguerite Helmers points out in her article “Hybridity, Ethos, and Visual Representations of Smokey Bear:”

“Clad in dungarees, Smokey Bear is shown to be a man of the people, a worker [...] The jeans were a clever visual rhetorical move on the part of the Ad Council because, while Smokey’s hat aligns him with [] authority [...] his pants make him one of the people.”

In other words, Smokey can be a hardass about fire safety when he needs to be, but he isn’t a narc. The visual symbol of the blue jeans gives Smokey a trustworthiness that he wouldn’t have if he were dressed only in the campaign hat. The pants imply to the viewer that Smokey isn’t just The Man talking down to them. His concern for the land is grounded in a concern for the people who can be harmed by uncontrolled wildfires.

Moreover, he carries no weapon to fight fires, or the people who cause them. Instead, he holds a shovel, which he often uses to pile dirt onto live coals, safely putting them out. Such a tool, and its associations with the responsible care of land, communicates the essence of Smokey’s approach to wildfires. Specifically, it implies that safely dousing fires before they get out of control is better than trying to contain active wildfires after they’ve already started.

The image of Smokey’s shovel, as part of his overall message, is therefore reassuring. It lets viewers know that, while wildfires are serious business, they can often be prevented with a few simple precautions. Together with Smokey’s campaign hat and dungarees, the shovel reminds viewers that everyone is called to play their part in those prevention efforts.

Now, if Smokey were only a mascot in appearing in a handful of public service announcements, there wouldn’t be much else to say about him. But in the years since his first appearance, he’s become much more than a character in an advertising campaign. As we’ll see, Smokey has been deliberately cultivated by the Forest Service to become a national icon—in the original sense of the word—and has even been put to work by the American public for uses the Forest Service never anticipated.

Smokey in the American Pantheon

As Larry J. Reynolds points out in his article “American Cultural Iconography: Vision, History, and the Real,” Americans have a long history of turning famous citizens into symbols of national values. In the eighteenth century, for instance:

“a new nationalism [] replaced religion as a dominant structure of thought and feeling [...] turning Washington into a secular icon for a new nation[.] Widely distributed images depicting heroic republican manhood produced patriotic citizens and resolved sociopolitical tensions[.]”

In other words, in the United States, images of well-regarded presidents and other historical figures have functioned as “secular icons” for a nation without an officially established religion.

Like illuminated paintings of Jesus in Orthodox churches, or statues of Siddhartha Gautama in Buddhist temples, images of Washington, Lincoln, Roosevelt, and other prominent Americans have been used as objects of focus and contemplation, designed to bring out particular feelings in the viewer—in this case, patriotism. In this way, they have been effective tools for “resolv[ing] sociopolitical tensions” between groups of citizens who couldn’t always rely on shared cultural backgrounds to solve their problems.

Throughout Smokey's lifetime, but especially during America’s bicentennial celebrations in the 1970s, the U.S. Forest Service has made an effort to include him in this tradition, positioning him as an American icon through posters, TV advertisements, and other media. This 1975 ad, for instance, puts Smokey on par with “great” Americans such as Washington, Lincoln, and Benjamin Franklin.

Interestingly, this spot makes no mention of fire safety! By this point in Smokey’s history, Americans were able to recognize him and his message on sight—the goal of the ad is not to repeat that message yet again, but to place it in the larger context of an iconography shared by most Americans, and thereby connect it more explicitly to symbols of American pride. In other words, this move by the Fire Service positions Smokey—and, by extension, environmental stewardship—as a key part of national identity.

Smokey the Icon

Like the cherry tree George Washington allegedly chopped down as a boy, and the pennies that Abraham Lincoln reportedly walked five miles to return to a customer he’d accidentally overcharged, Smokey’s shovel, hat, and other implements are powerful mythological images that can communicate messages about important values without the need for words.

Small wonder, then, that individual citizens have at times adopted Smokey and his tools to communicate their own ideas—not all of which align with the Forest Service’s original message.

Particularly in the years surrounding the Vietnam War, which brought issues of forestry and conservation into sharp focus, people on all sides of the growing culture wars used the image of Smokey Bear to share their own beliefs about how land ought to be treated. In one chilling example, some Air Force pilots ironically adopted Smokey as the unofficial mascot of Operation Ranch Hand, the military’s project to defoliate Vietnamese forests by dousing large areas in chemicals such as Agent Orange. Posters found on military bases at the time show Smokey above an altered version of his famous tagline: “Only YOU can prevent a forest.”

Smokey’s image was also subverted back in the U.S., where he played a role in the popular environmentalist novels The Monkey Wrench Gang and The Milagro Beanfield War. Both books feature scenes in which angry civilians deface images of the bear, as a symbolic protest against what they perceive as the federal government’s interference in the natural landscape.

But perhaps the most enduring use of Smokey Bear outside of an official context comes to us from poet Gary Snyder, whose 1969 poem “Smokey the Bear Sutra” pushes the icon-ification of the character to the extreme. Modelled off of Buddhist holy texts, the poem depicts Smokey as a reincarnated buddha, who has entered into the world to protect people and the environment from the harm caused by greed and ignorance.

Snyder accomplishes this by writing about Smokey’s accessories in a style that reflects traditional descriptions of the symbolic objects associated with particular icons, such as lotus flowers, flaming swords, hand gestures, and so on. Snyder depicts Smokey, for instance, as:

“Bearing in his right paw the Shovel that digs to the truth beneath appearances; cuts the roots of useless attachments, and flings damp sand on the fires of greed and war [...] Wearing the blue work overalls symbolic of slaves and laborers, the countless men oppressed by a civilization that claims to save but often destroys; Wearing the broad-brimmed hat of the west, symbolic of the forces that guard the wilderness, which is the Natural State of the Dharma and the true path of man on Earth[.]”

In other words, Snyder offers his own spin on the iconography of Smokey Bear. He riffs on the established meanings of the symbols associated with the character, in order to recruit Smokey as an avatar for his own causes, such as pacifism and anti-capitalism.

Thus, like the Forest Service, Snyder continues the tradition of elevating Smokey to the status of an icon—an image that people can reflect on in order to cultivate certain values, thoughts, or states of being.

How to "Get Your Smokey On"

So what does Smokey’s success mean for us as marketers and storytellers? What can we learn from the character’s initial conception, use in campaigns, and ongoing evolution that can help us make our own work more effective?

For one thing, Smokey makes it clear that it’s important to think very carefully about the symbolism of the elements in your organization’s visual identity, and the context in which that identity will be interpreted.

Albert Staehle and other early illustrators thoroughly considered the wants, needs, and beliefs of their mid-century American audience, and combined visual symbols that would appeal to the right people by striking the perfect balance between authority, solidarity, and pragmatism. In the process, they created a character that felt immediately trustworthy to many, and has had a huge impact on American environmentalism.

.jpg?width=640&name=640px-Smokey_Bear_Fire_Prevention_School_Visit_(17159352622).jpg)

Even if your organization doesn’t have a traditional mascot like Smokey, at some point you will have to make decisions about the visuals attached to your brand—knowing that those visuals won’t be seen in a vacuum.

Ask yourself: what will particular color choices mean for the people who will be interacting with this brand? What’s going on in the world that impacts the meaning of the photos you use? What images have metaphorical connections to what you’re trying to say, and how can you use those connections to emphasize your message?

In addition, Smokey’s success points to the storytelling power of concrete, specific images. Smokey doesn’t deal in abstract ideas. He wears and carries solid objects: a hat, a pair of dungarees, and a shovel. He is concerned with fires. He points to You as the solution. If he were instead to stand in front of a blackboard and lecture us about the process of combustion, we’d rightly fall asleep.

Whether in a short story or a TV spot, images of concrete, physical objects give people something to hang onto, and make the underlying message easier to grasp—hence the popular writerly advice to “show, don’t tell.”

Crisp, understandable details make stories more compelling—see, for instance, how Gary Snyder latched onto Smokey’s clothes and tools to express his message of ecological and social responsibility. Airy abstractions, on the other hand, can leave people bored and unconvinced.

In general, where is your current visual identity vague or nonspecific? Are you using your visual identity as an opportunity to stand out—or does your brand melt into the ever-growing slurry of bland, non-committal corporate design?

More specifically, see if there are opportunities for your brand to incorporate concrete images into its visual identity. Are there running themes in your copy that suggest some particular image? Is there an object that could act as a powerful symbol for your organization’s goals? In other words, what is your brand’s “Smokey hat”?

Think deeply about the symbolism of your brand’s visual presence, and you’ll be well on your way to creating your own enduring, powerful icon.