“Let’s table this and take the conversation off-line. I’d like to sync up to gain some actionable insights into pain points, and figure out the best way to drive value moving forward. We need to elevate our messaging by leveraging our unique differentiation…”

Like a twisted Zen master, your boss drones on, spinning out corporate koans that seem designed to leave you lost and confused. Adrift in the steady, relentless flow of non-language, you somehow feel both bored and anxious at the same time. There’s nothing solid here for your attention to grab on to, but it all seems vaguely important…

Looking at his jaw clack open and shut, you can’t help but think of the first time you saw a marionette as a child—that cold, creeping sense of the uncanny that wormed its way up your spine as you gazed into those painted wooden eyes and realized that nobody was home.

Is there anybody at home in the body of the man who just unironically used the phrase “apply these learnings”? Could a thinking mind, a living spirit, truly have expressed a desire to “deliver on our customer-centric action plan”? Or are you the only conscious being on this Zoom call?

“Jenn, what’s your input?”

A tense moment of silence—seven disembodied heads stare back at you from the glowing screen of the Macbook Pro stacked on your childhood copy of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince. With dawning horror, you feel something hatch in the back of your throat. It wriggles its way up your tonsils, skitters over your tongue, and buzzes out into the world:

“If we want to move the needle here, we’re going to have to do a deep dive and find our true north. That’s just table stakes…”

Buzz, Buzz

Buzzwords. Corporatespeak. Jargon. Whatever you call it, we love to hate it—that weird collection of sweaty, startup-flavored words and phrases that we all poke fun at, even as we find ourselves falling back on them throughout the day.

Which is strange, when you think about it. Reactions to buzzwords tend to range from mild annoyance to outright loathing; and while someone does occasionally mount a qualified defense of using corporate jargon in certain contexts, you’d be hard-pressed to find an office worker who considers terms like “ideate” or “drill down” to be intrinsically valuable, meaningful, and not-yucky.

So why do these hated words and phrases stick around? How do they come to dominate our meetings—or even leak out into the wider world through our company websites, ad campaigns, and content?

Clearly, spammy business language does serve some kind of purpose at work and in the broader culture. But what is that purpose? Is it mainly about increased efficiency, as some buzzword defenders claim? Or is something more going on when we tell a colleague we’ll “circle back after the standup?”

To find out, we’ll have to explore the nature of language itself—how it works, what it’s for, and how we use it in our daily lives.

Language Games and Lebensformen

One of the most common complaints about buzzwords is that they have no definite meaning—that they are fuzzy or wishy-washy, and don’t actually communicate any certain idea from one person to another.

But, as philosophers of language have begun to realize over the past hundred years or so, the same can arguably be said for enormous chunks of our vocabulary, if not for language as a whole.

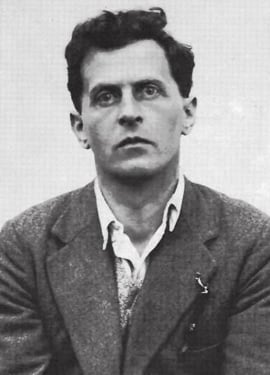

Ludwig Wittgenstein, arguably the most influential philosopher of language to date, spent decades trying to understand how language worked. Ultimately, he came to believe that “In most cases, the meaning of a word is its use”—in other words, that meaning is not some objective, out-there thing a word has or points to, but instead an emergent property of how people employ that word in everyday speech and writing.

To put it another way, the meaning of a word is connected to the goal that a person is trying to accomplish by using it in conversation.

Wittgenstein identified many of the common goals of communication in his Philosophical Investigations, famously referring to them as language games—the shifting sets of intentions that people have in mind when using language, which can vary depending on context. Language games, he thought, were part of the larger patterns of collective behavior he called lebensformen, or “forms of life,” the sum total of explicit and unspoken rules a person follows while participating in a given society or culture.

What does all of this have to do with buzzwords? By looking at corporatespeak from Wittgenstein’s point of view, we can start to frame our original questions in a way that will lead us to a deeper understanding not only of the words themselves, but of the corporate culture that spawned them—and its eventual impact on how we do marketing.

To put it bluntly: what exactly is the language game we’re playing when we press-gang the poor verb “ask” into service as a noun? And what do the rules of that language game tell us about the “form of life” of the modern business world?

Garbage Language

In a recent review of Uncanny Valley—Anna Weiner’s memoir about startup life in the mid-2010’s—book critic Molly Young offers a bleak take on office life in the era of surveillance capitalism, and on the corporate lingo that saturates so many of our meetings, emails, and phone calls.

Taking a cue from Weiner, Young refers to these words and phrases as “garbage language” that stinks up our conversations, taking up space and adding nothing of value.

Yet for all its vagueness and puffery, Young argues that garbage language does, in fact, serve a definite purpose for the people using it—in other words, that buzzwords are a key part of a language game that many office workers are forced to take part in:

“It is obvious that the point [of garbage language] is concealment [...] In an environment of constant auditing, it’s safer to use words that signify nothing and can be stretched to mean anything, just in case you’re caught and required to defend yourself.”

To put that in Wittgensteinian terms, one of the most common language games in a modern work setting—in which employers and even clients may have direct access to company-monitored email threads, Slack channels, and servers, along with indirect access to employees’ public-facing social media accounts—involves paradoxically using language to avoid saying anything meaningful, rather than risk making an actual statement that could be found and punished later.

Like ninja throwing smoke bombs to escape an enemy stronghold, workers stuck in this dysfunctional lebensform naturally become masters of misdirection, expertly deploying clouds of nonsense that create the appearance of a happy-go-lucky workaholic, all while carefully concealing the real human being underneath. In this zero-sum language game—part of a larger “form of life” that can be harsh on honesty—the winner is the one who can stretch the least amount of information across the greatest number of words.

While Young’s assessment may be grim, it’s hard to deny completely. Most of us, at some point in our careers, have been forced to sit through the kind of meeting she describes in such detail—an endless back-and-forth exchange of buzzwords where “attendees circle the concept of work without wading into the substance of it.”

This hijacking of language is bad enough when it’s contained to our workplaces and conference calls. But what about when it spills over into the wider world? What happens when we let fear dictate our marketing?

"Mercury brakes have larger brake-lining area."

As a creative or marketing director, you have multiple audiences to consider when concepting, creating, and approving work for your brand. There is, of course, the end-user who will apply your product or service in their day-to-day lives. But in between you and them lies a small army of creative directors, middle managers, and executives, many of whom may have to sign off on your idea before it even moves into production—and all of whom are playing a subtle language game that incentivizes people to say as little as possible while taking up the largest amount of space.

In other words, you may have a brilliant idea that speaks directly to your customers’ deepest wants and needs—something exciting and new that will leave people eager to buy what you’re selling or donate to your cause. But no matter how good that idea is, any potential benefit it may bring is going to be weighed against the anxieties it provokes in powerful people who have built careers by systematically avoiding excitement and novelty.

And when these anxieties win out over a desire for great creative work, you get bland, jargon-y marketing materials like the above 1959 ad for Mercury cars.

In this easily parodied advertising style, we see what happens when a company’s favorite buzzwords slip out of the boardroom and find their way into public-facing communications. This dull, over-long advertisement offers viewers a relatively technical description of a Mercury’s advanced braking capability—while saying little about how that feature translates into a felt benefit that will help people achieve their own goals.

As a result, while the spot was possibly very interesting for the engineers who built the car, and the executives who had the final say over whether it would be aired, it did very little to address the reasons why people actually buy cars, which are grounded in relationship and emotion.

In her book review, Young shares a far crazier example of technical jargon run amok, in her story of a subscription-box service aimed at recreational runners—which was selling packets of maple syrup as “low-glycemic-index sports fuel.”

Unrelatable or spammy marketing materials like these are the end result of creatives and marketing directors making work that satisfies the needs of the office language game, providing plenty of cover for one’s ass by avoiding saying anything of consequence. In other words, fear breeds boring, or even nonsensical, marketing.

Breaking Free of Buzzwords

To be fair, there are clear benefits to the approach outlined above. The Mercury ad is, if nothing else, inoffensive. Buzzwords and jargon may put viewers to sleep, but at least they won’t provoke the massive backlash seen in response to recent tone-deaf ads for Pepsi and Ancestry.com.

By that same token, however, ads that rely so heavily on jargon or buzzwords—that play into the internal office politics of the companies producing them, at the expense of their ability to communicate with core audiences—lose the opportunity to make any sort of impact at all. A safe, meaningless campaign may prevent the CMO from throwing a hissy fit, but it won’t stand a chance of sparking a national conversation or changing an industry.

Good storytelling involves risk: the willingness to create meaning, rather than destroy it, and the vulnerability that comes with that choice. To move people, an organization must be willing to make actual statements in its marketing efforts—and that, ultimately, is going to require willingness from the people in charge of those efforts to approve work that doesn’t always feel completely safe.

Now, we’ll be the first to admit that there are no easy answers here. Not every work environment is going to tolerate open, honest expression, and not every employee can afford to break the buzzword bubble. But those of us in positions of authority, either on the client side or the agency side, do have a choice to make when deciding how to share a brand with the wider world.

On the one hand, we can give in to the temptation to conceal by approving campaigns which say very little, and avoid making statements that could actually cause change. Or, we can take the uncomfortable step of making a bold claim about how our organization can improve lives—and reap the rewards of a real story.