It looked like apple juice. It tasted like apple juice. Sure, it was technically made of beet sugar, cane sugar syrup, corn syrup, and various other non-apple ingredients—but what did that matter? What harm could there be in labelling and selling such a product as “100% apple juice”?

That was the gamble that executives at Beech-Nut took in the early 1980s—just a few years before the federal government sued them for attempting to defraud and mislead the public with a phony product. As part of the fallout from the fake-apple-juice case, Beech-Nut paid $140,000 in investigative costs to the FDA, plus a $2 million fine. In addition, two Beech-Nut executives were found guilty of attempted fraud, and spent time in prison.

Beech-Nut’s actions offer a straightforward example of unethical marketing tactics: telling deliberate lies to trick customers into buying something other than what they think they’re getting. But the line between ethical and unethical marketing behavior is rarely this clear. Many marketing tactics which we might think of as gross or unsavory are not, strictly speaking, illegal—you can do quite a bit of unethical marketing before landing yourself in court.

That being the case, why should we care about making ethical marketing choices in the first place? Why bother when, as marketing education resource Marketing Schools makes clear in its discussion of ethical marketing principles, “Unethical advertising is often just as effective as it is unethical[?]” Why go beyond questions of effectiveness and put in the extra effort to think about the moral standing of our work?

In this post, we’re going to explore the ins and outs of marketing ethics: what distinguishes ethical marketing from unethical marketing; how ethics relates to brand storytelling; and why, from a practical point of view, it is very much worth our time to ground our marketing strategies in good ethics.

The Death of Joe Camel

Besides approaches like Beech-Nut’s, which obviously violate existing consumer protection laws, what kinds of marketing count as unethical? How do we define “unethical marketing” in the first place?

Business ethicists have been debating these questions for decades, and still sometimes disagree about how to apply ethics in specific marketing situations. Even so, it’s generally agreed upon that deception and manipulation are clear examples of bad behavior. Since trust between buyers and sellers is such a vital part of a healthy market-based economy, eroding that trust by lying about the nature of a product or service is a big no-no. As the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy puts in in its overview of business ethics:

“manipulative advertising can be understood as advertising that attempts to persuade consumers, often (but not necessarily) using non-rational means, to make irrational or suboptimal choices, given their own needs and desires.”

Broadly speaking, then, unethical marketing is advertising or other communication designed to trick people into buying things that are not beneficial to them, or even downright harmful. This twisting of the truth can take many forms, and can range in severity from omission of important information to outright lies—but the underlying problem is the same.

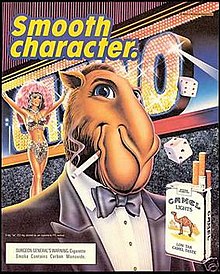

Under this definition, it’s easy to see why Joe Camel, the retired mascot for Camel Cigarettes, has become the poster child for the worst sort of marketing behavior.

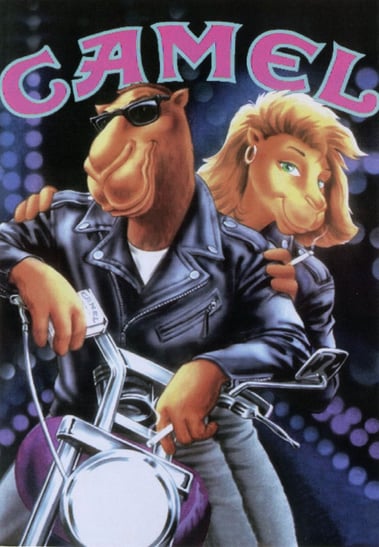

For years prior to his 1997 cancellation, U.S. anti-smoking activists protested the use of Joe Camel in print advertisements, on the grounds that his posters—which featured the cartoon camel driving expensive sports cars, wearing fancy suits, dating beautiful women, and rocking a pair of sunglasses, always while smoking a Camel cigarette—were designed to appeal to children, encouraging them to associate smoking with all things cool.

To the bitter end, the company maintained that Joe Camel was designed to appeal to adults, rather than kids. But even if this was Camel’s true intention all along, Joe still stands out as a prime example of shady marketing tactics in action.

Like the Marlboro Man before him, Joe Camel encouraged people to associate cigarettes with a certain brand of masculinity—to see smoking as a way to be a “Smooth Character,” as the brand’s tagline put it. In other words, whether or not it was meant to get kids hooked on cigarettes, the Joe Camel campaign was undeniably a “non-rational” series of messages, aimed at getting consumers “to make irrational or suboptimal choices.”

It was “non-rational” because smoking does not, in fact, correlate in any meaningful way with owning nice cars, dressing fashionably, or hooking up with gorgeous people—yet the design of the posters implied all of these things, even if the copy never stated them outright. What’s worse, these posters tried to convince people to make the “suboptimal choice” of ingesting a product that, by the 1980s, was well-known to be highly addictive and to contribute to an increased risk of cancer.

By the late 90s, the problems with the campaign had become obvious to many consumers, and Joe Camel had worn out his welcome. The character was skewered by South Park, not long after president Bill Clinton’s chief policy advisor Bruce Reed summarized the end of the campaign by saying: “Joe Camel is dead. He had it coming.”

Defining Ethical Marketing

If unethical marketing uses deception to exploit vulnerabilities, ethical marketing should do just the opposite—present all relevant information in a clear, straightforward manner, in the hope of encouraging people to buy products and services which will help them meet their own “needs and desires” in some tangible, non-harmful way.

While it might be easier to point out examples of sleazy marketing ploys than to define what exactly makes for good, morally defensible marketing, the American Marketing Association has at least tried to provide a framework for ethical decision-making in its public Code of Conduct. Among other things, the Code calls on marketers to:

- Do no harm, by sticking to legal marketing tactics,

- Foster trust in the marketing system, by telling the whole truth in all communications, and

- Embrace ethical values, including honesty, responsibility, fairness, respect, transparency and citizenship.

While no set of rules is perfect, the AMA Code of Conduct does provide a good starting point for marketers hoping to evaluate their current strategies and tactics, or develop ethically sound marketing campaigns in the future. And that is something that every marketer should strive to do, for a surprisingly practical reason…

The Value of Truth

While committing to ethical marketing practices is a worthwhile project in itself, this kind of behavior isn’t just for the goody-two-shoes of the world. Ethical marketing is actually a vital part of a strong, long-term marketing strategy that can withstand the inevitable ups and downs of the market—and weather a company’s own mistakes.

To put it bluntly, honesty pays.

One of the clearest examples of the power of ethical marketing comes from Domino’s, the pizza chain that made a pivot to transparent advertising in 2010—and has since raked in an additional $12 billion in brand value.

Prior to 2010, the brand faced a number of PR disasters, including chronic bad reviews on social media and a viral video of an employee sneezing on a pizza. Initially, the company tried to respond by minimizing the damage, ignoring the many reviews that compared its crust to “cardboard” and pointing out that the video had been a teenage prank.

This approach, while hardly the most unethical marketing strategy we’ve explored in this post, still fell short by trying to gloss over the truth—that the quality of the pizza had tanked in recent years, and was only getting worse. Predictably, people remained unimpressed, and sales kept dropping.

Then, in 2010, the company released a video in which key executives, company chefs, and employees owned up to the negative feedback, and vowed to make its pizza taste good again. In other words, Domino’s acknowledged its problems, apologized for the loss of quality, and promised to make up for it.

In combination with the brand’s leading digital experience, the move helped make Domino’s into the number one pizza retailer in the country—and marks one of the few moments in history when a major restaurant chain made an unambiguously ethical marketing decision.

Far from trying to “manipulate” people by hiding the truth about its bland, awful pizza, the company promoted it, even going so far as to display some of its worst reviews on enormous billboards in Times Square. In doing so, they treated their disappointed customers as human beings with functioning taste buds and opinions that mattered, rather than as a gullible, faceless collection of mouths and wallets.

The video won back the cautious trust of jaded former customers, and real improvements to the quality of the pizza sealed the deal. None of it would have been possible without that initial switch to a more ethical marketing strategy.

Be a Trustworthy Guide

We’ve written before about how successful brands position themselves as Mentors to their Audience-Heroes, offering people the guidance and resources they need to fulfill their own goals. Successful brand storytelling, in other words, demands an ethical marketing approach grounded in transparency and trust.

When a brand commits to a storytelling-based marketing strategy, ethical marketing becomes essential: a Hero has to trust their Mentor if they’re going to complete their story. Where this trust is damaged or missing in the first place, there is very little chance for a brand to become a regular, welcome part of a customer’s life.

By contrast, when a brand is open and honest about the nature of its products and services, its goals, and even its shortcomings, it builds trust with audience members who see that they are being treated as real people with unique ambitions and goals. Over time, good ethics builds good relationships—and offers your brand the chance to become a critical part of your audience’s story.