American writer and comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell has had an enormous influence on the way modern audiences think about stories and storytelling.

.jpg?width=361&height=425&name=Joseph_Campbell_at_Feathered_Pipe_Ranch%2c_Montana_(cropped).jpg)

Through popular books like The Hero with a Thousand Faces and The Masks of God, as well as a widely distributed interview series with journalist Bill Moyers, Campbell introduced millions of Americans to the myths and legends of cultures around the world—and the recurring themes that seem to tie many of them together. Campbell argued that all of the world’s myths share an underlying structure he called the Monomyth, or Hero’s Journey, which involves a Hero leaving home, having adventures in some other place, and returning to their community with a gift to share.

Over the last few decades, this structure has come to dominate much of popular storytelling, and Hollywood cinema in particular. With so many bestselling novels and international blockbusters using the Hero’s Journey to great success, it would seem at first glance that Campbell was right—that most or all great stories can be distilled down to a formula, which is universally applicable across time and place.

However, as we’ll be exploring in today’s blog post, Campbell’s theories aren’t always a perfect fit for the needs of storytellers in the real world. The Hero’s Journey is not as universal as Campbell would claim—and the framework is weighed down by Campbell’s own antisemetic and sexist thinking.

The Hero’s Journey is a powerful, but complicated, tool. If we as storytellers are to use it effectively, we’ll need to fully understand both its benefits and its drawbacks.

Gaps in Campbell's Theory

In a 2021 article for the Journal of Screenwriting, film writer and director Glenda Hambly argues that the Hero’s Journey does not, in fact, apply to the stories and myths of all cultures around the world. According to Hambly, Campbell

“projected Anglo-Western storytelling and cultural values onto Indigenous mythic narratives, which in fact have very different storytelling norms and serve a very different purpose to the individualistic striving for self fulfilment which he identified [as the key to all storytelling].”

In other words, Campbell cites superficial similarities between myths of different cultures as evidence for the claim that the stories of all cultures share an underlying purpose, i.e. the dramatic reenactment of the individual’s quest for self fulfillment.

In the process, he ignores overwhelming ethnographic evidence that the very idea of an atomized, individual “self” separated from clan, species, etc. is a relatively new one in the history of human thought, and that such a striving self is not a central feature in stories from many parts of the world.

To illustrate her point, Hambly cites the Arrente First Nation’s initiation ceremony, which Campbell points to as a clear example of the Hero’s Journey in action. Campbell interprets the ritual—which involves a boy leaving home, enduring trials, and returning to the community as a man—as dramatic reenactment of the same Monomyth structure that underlies European and American folktales of individual self-actualization. However, as Hambly points out, the Arrente ritual actually serves a very different purpose:

“For Campbell, the hero’s journey is individual, and the knowledge he gains is self-generated. Campbell expresses a view of initiation that is rooted in the western tradition, congruent with western psychologized notions of selfhood. From a First Nation Australian viewpoint, initiation is a collective achievement. [According to anthropologist W. E. H. Stanner,] ‘No boy “becomes” a man; other men “make” him a man.’”

By tweaking the meaning of the Arrente ritual to better suit his preconceived theory, Campbell misses the actual point of this story in the context of Arrente society. The elders and boys reenact this myth not so that the boys’ selves can discover themselves, but so that the elders can actualize the boys’ selves by integrating them more fully into the community. Arrente boys cannot become men outside of the context of their community—it is their involvement with and relationship to the community which makes them men in the first place.

Here, and in other storytelling traditions from around the world, the striving self at the heart of Campbell’s Hero’s Journey is conspicuously absent. And while it is true that the framework has demonstrated broad appeal across many cultures, these exceptions demonstrate that it is not a universal feature of human storytelling after all.

Campbell, History, and Antisemitism

Moreover, Hambly isn’t the only thinker to’ve noticed problems with Campbell’s emphasis on the individual at the expense of the community.

In a 1998 article for the Journal of the American Academy of Religion, interdisciplinary philosopher Martin Stanely Freidman contends that Campbell’s individualistic thinking is a product of his Jungian roots. Friedman argues that, like his inspiration Carl Jung—a thinker who also erased differences between cultures while constructing his universal theory of human psychology—Campbell:

“uses myth not only to see metaphysics in terms of psychology but also, as he explicitly points out, psychology in terms of metaphysics [...] the total effect is that of the psychologizing of myth, if we use ‘psychologizing’ in the broader sense of finding myth in the depths of the soul rather than in the reality of communal life.”

Campbell, in other words, argues that the power of myth comes from its grounding in the psyche of the individual, rather than in “the reality of communal life.” Myth, for Campbell, is universal, rather than particular—the differences between the myths of various cultures matter less than the similarities that he can find in (or project onto) them.

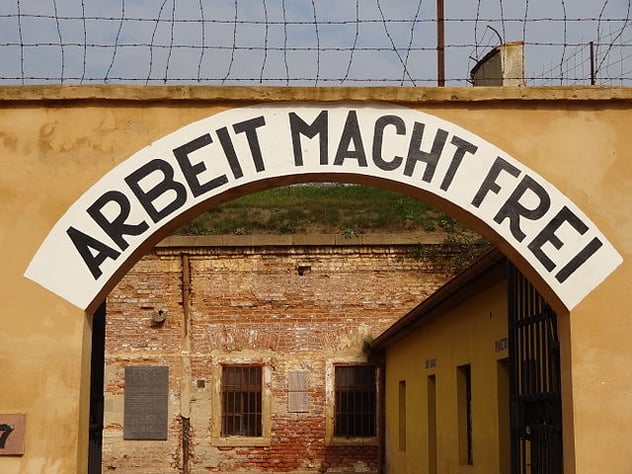

The implications of this idea are very serious. According to Friedman, Campbell’s tendency to universalize human experience and erase difference prevented him from engaging seriously with historical tragedies such as the Holocaust as “touchstone[s] of reality.” That is, Campbell’s theories lead him to “psychologize” historical tragedies, lumping them all together essentially identical beats in the endlessly recurring, never fundamentally changing Monomyth.

Viewed in this way, the meaning of the Holocaust become less about the unique evils it revealed and the particular communities it devastated, and more about how the individual relates to tragedy in the abstract. As Friedman puts it:

“Our concern [...] with his reduction of the Shoah [Holocaust] to an internal, psychological matter, lies in the fact that it is closely linked with his psychologizing of myth—his rejection of history, the event, the unique, and the particular in favor of the internal, the psychological, and the universal.”

In other words, from Friedman’s point of view, Campbell is blotting out differences that really matter—blurring the lines between the unique myths, histories, and events that take place within “the reality of [a particular] community life”—extracting these stories from the contexts in which they have their truest meaning—in order to turn them into tools for the development of individual psyches.

In the process, he robs the stories of their original purpose as “touchstones” that weave individuals into broader communities, and affirm the reality of lived experience over abstract theory—and robs himself of the opportunity to more fully understand particular communities and the everyday world by studying them deeply and appreciating their differences.

This tendency, considered alongside more direct evidence of antisemitism gathered from Campbell’s personal interactions and papers, should give us pause when we consider whether and how we should let Campbell’s theories influence our work.

Campbell on Women

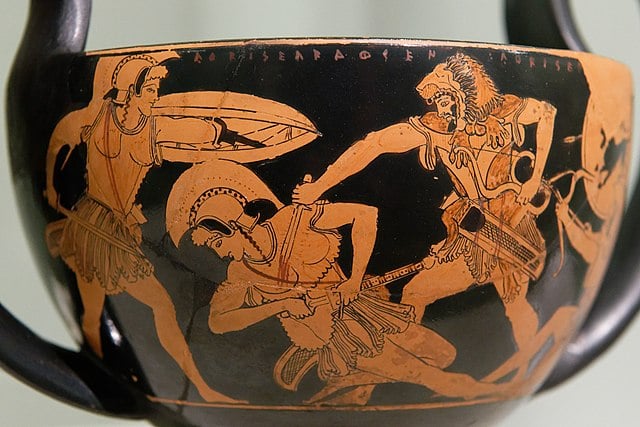

In addition, Campbell’s habit of elevating the universal over the particular also led him to develop a broad, fairly reductive understanding of women’s role in myth.

Mary Lefkowitz, classics scholar, argues in a 1990 article for The American Scholar that Joseph Campbell’s work reduces women to the role of mothers, caregivers, and muses—in other words, positioning them mainly as supports for the men who more frequently act out the Hero’s Journey. As she puts it:

“The Goddess who represents all women is the creator, and her own body is the universe; hence sexuality and childbirth are sacred, so that even ordinary acts of lovemaking, and certainly marriage, are forms of worship [...] It is clearly the powers of the female body that Campbell wishes to celebrate, and not the force of the female will or determinations of mind. [Campbell’s archetypal Goddess is] a projection of an ideal European housewife, whose sexuality exists only to serve a larger purpose of creating and nourishing. In fact, she exists primarily to serve and inspire mortal men.”

In other words, by focusing primarily on what most women have in common—i.e. the capacity to give birth and other “powers of the female body”—Campbell glosses over what makes individual women unique—their particular wants, needs, and abilities.

_(14752822495).jpg?width=397&height=599&name=Heroes_of_the_dawn_(1914)_(14752822495).jpg)

In so doing, Campbell erases important differences between individual members of a category, in the same way that Hambly and Friedman point out. In his discussions of gender, Lefkowitz argues, Campbell consistently forces particular instances to fit his own “European” ideas, as he also does with myths and historical events.

Far from being a truly universal account of women or femininity, Campbell’s explanation of the role of women in myth is grounded in both a patriarchal understanding of gender relations and a European cultural understanding of women’s capabilities.

Reevaluating the Hero's Journey

So, with all these knocks against Campbell and his work, why bother with the Hero’s Journey at all? Why would we as storytellers continue to refer back to it as an inspiration for our branding, marketing, and communications work? Why not just chuck the whole problematic business aside, and try something else?

While it is undeniable that the Hero’s Journey fails as a universal theory of human storytelling across times, places, and cultures, it is also true that stories grounded in the Hero’s Journey have proven to be massively successful and beloved in many places and many cultures around the world. The vast majority of the all-time top-grossing films at the international box office, for instance, are structured with the Hero’s Journey in mind.

Still, as Hambly points out, “Hollywood’s marketing genius, financial might and control of distribution and exhibition no doubt played a major role in the successful export of classical design, making it the most popular screen narrative form internationally [...] Screenwriting academics who choose to privilege Hollywood’s classical design above any other can claim [the Hero’s Journey] is the most popular screen narrative form internationally, [] they should not continue to claim it is universal.”

The Hero’s Journey is not an all-purpose tool—but, for better or worse, it does have a place in our global culture.

That said, the fact that a storytelling theory performs well doesn’t give us a blank check to employ it however we see fit. As marketers, we are responsible for the stories we tell, and should remember to keep ethics at the front of our minds whenever we are constructing a brand narrative, content strategy, or other piece of storytelling for our clients.

Can we recognize the merits of Campbell’s work, while critically questioning his beliefs about the essential sameness of people and cultures across time and place? Can we use the Hero’s Journey to help us create stories that will appeal to broad audiences—without erasing meaningful differences, or tricking ourselves into believing we’ve found the ultimate answer to all of our storytelling challenges?

If we want to tell stories that unite people around common causes—while meeting the needs of a constantly diversifying culture—we’d better.